PICTURING THE WORLD:

Snapshots of a Translocal Cantonese Peruvian Ecumene, Circa 1924

Ana Maria Candela, Binghamton University

The Album

|

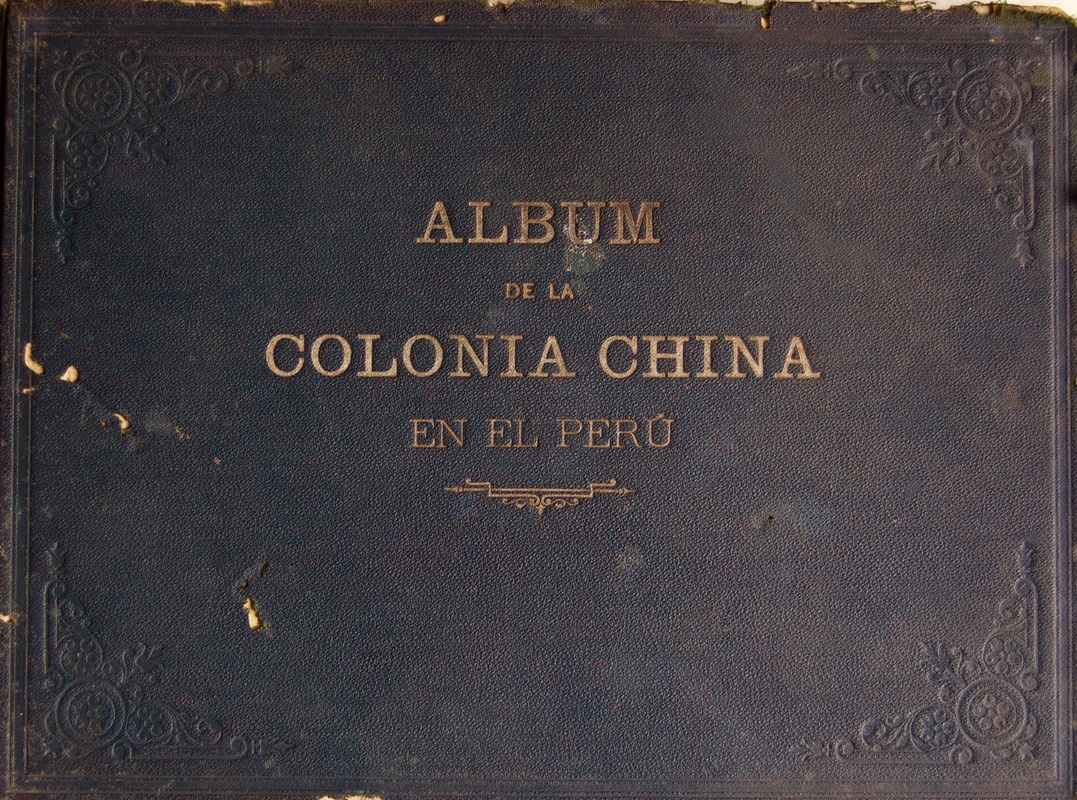

In 1923, Tsung Yee Loo, the Chargé d'affaires for the Republic of China in Peru, collaborated with Aurelio Pow San Chia, Fon Shan King and Tomas Yui Swayne, three prominent Lima-based Cantonese merchants, along with Francisco Leon, the Director of the Lima-based newspaper The Voice of the Chinese Colony (La Voz de la Colonia China), to gather information and photographs from prominent Chinese businessmen for the publication of a community album that would be presented to the members of Congress. The album would “allow the rest of Peru, particularly the officials, high commerce and Lima society, to marvel at the commercial prosperity and achievements attained by the Chinese in Peru through hard work and action, which is always friendly towards Peru” (Colonia 1924, 9). Published in 1924, The Chinese Colony in Peru: Representative Men and Institutions: Its Beneficial Action in the National Life appeared just as an informal two-year suspension of Chinese migration came to en end, the result of a failed effort to pass a formal law banning Chinese migration to Peru. The album reflected a strategic attempt by Chinese political and economic elites to counter anti-Chinese sentiment by crafting an image of a prosperous foreign merchant community that brought great economic benefits to its host nation.

|

The community album emerged as a popular genre during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Frequently produced to bolster a city’s commercial and industrial enterprises, these albums portrayed prominent businessmen and their shops and factories (Hoffecker 1983, 37-38). Racial, ethnic and immigrant populations seeking to craft an integrated image of their communities to claim inclusion within a broader urban or national context also took up the genre, creating albums featuring their own economic elites, businesses and community associations (Young 2013). As a minority community album, The Chinese Colony in Peru of 1924 is a popular primary source used by historians to gather information on Chinese commercial elites, their businesses and associations, the social and economic processes that enabled Chinese to settle and flourish in Peru and the cosmopolitan imaginaries they crafted to claim social and economic inclusion as foreign nationals (Derpich 1999; Lausent-Herrera 2000; McKeown 2001).

This exhibit makes The Chinese Colony in Peru accessible to readers and also provides a reading of the album as a snapshot of a translocal Cantonese Peruvian ecumene. This translocal reading suggests ways of conceptualizing the history of Asians in the Americas and ways of engaging with questions of traffics, territories and modes of belonging (i.e. citizenship) that do not default into methodological nationalism. Rather, it suggests a way to take the social, cultural and geographic complexity of migrant worlds as both the point of departure and the end goal in the conceptualization of those histories. By shifting the analytic lens away from a focus on the album’s narrative of integration, traces of this translocal world become more visible. When read critically as a snapshot of a bigger Cantonese Peruvian ecumene, the album offers a glimpse into the social, physical and imagined geographical contours of a translocal migrant world that is all too easily eclipsed by the consolidation of bordered and settler nation states during the long 19th century.

This exhibit makes The Chinese Colony in Peru accessible to readers and also provides a reading of the album as a snapshot of a translocal Cantonese Peruvian ecumene. This translocal reading suggests ways of conceptualizing the history of Asians in the Americas and ways of engaging with questions of traffics, territories and modes of belonging (i.e. citizenship) that do not default into methodological nationalism. Rather, it suggests a way to take the social, cultural and geographic complexity of migrant worlds as both the point of departure and the end goal in the conceptualization of those histories. By shifting the analytic lens away from a focus on the album’s narrative of integration, traces of this translocal world become more visible. When read critically as a snapshot of a bigger Cantonese Peruvian ecumene, the album offers a glimpse into the social, physical and imagined geographical contours of a translocal migrant world that is all too easily eclipsed by the consolidation of bordered and settler nation states during the long 19th century.

The Method

This translocal reading of the album The Chinese Colony in Peru is grounded in a world history as method approach (Dirlik 2005). This approach challenges us to shift our conceptual focus from nations and transnationalism to places and the translocal processes and human motions that define and connect places. Such an approach compels us to account for a proliferation of places and spaces, including supranational and subnational spaces, such as diasporic spaces, borderlands, contact zones, domestic spaces, rural and urban spaces, cores and peripheries, the uneven spaces of development and underdevelopment, and perhaps also the spatial imaginaries that help to animate human actions and historical processes. A translocal method also challenges us to deconstruct structural totalities, such as civilizations, nations, regions, empires, capitalism and markets, by paying attention to the human activity and social actors that fill out those spaces and processes. The point of a translocal approach is not simply to deconstruct the conventional spatial containers of history; it is "to view the past differently, to open up an awareness of what was suppressed in a historiography of order, and to take note of the importance of human activity, including intellectual and cultural activity, in creating the world" (Dirlik 2005, 404). If we are to embrace a translocal world-historical approach to the study of Asians in the Americas that moves us beyond the limits of methodological nationalism and transnationalism, which too often deconstruct the nation only to end up reifying it by defaulting back to nations as the central analytic units of history, we need radically new conceptualizations and categories to think through.

Borderlands approaches emphasizing translocal and transnational histories played a critical role in fomenting the recent expansion of scholarship on Asians in the Americas. Scholars working on Asians in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands have produced a number of recent works that shed light on borderlands as a site of intersection between global and local systems of migration, the role of anti-Asian violence in the consolidation of state sovereignty, the rich interracial histories that defy racialized border making, and the formation of ethnic commercial and human trafficking circuits that subvert exclusion acts by moving through borderlands (Romero 2011; Delgado 2012; Schiavone Camacho 2012; García 2014; Chew 2015; Castillo-Muñoz 2016; Chang 2017; Gonzalez 2017). Transpacific and hemispheric frameworks have also played an important role in shaping the new scholarship on Asians in the Americas. These works have situated the history of Chinese coolies in the Americas in relation to hemispheric and Atlantic world histories of black slavery; examined Chinese exclusion acts, Orientalism and yellow peril as hemispheric processes; explored empire as another spatial formation shaping migrant lives; analyzed patterns of remigration across the Americas; and detailed the importance of transpacific homeland ties in shaping Asian lives and identities in the Americas (Azuma 2005; Jung 2006; Yun 2008; Lopez 2013; Schiavone Camacho 2012; Seijas 2014; Young 2014; Lee 2015). This recent scholarship reveals the emerging field of study on Asians in the Americas to be a field defined by efforts to conceptualize migrant histories as multispatial and multiscalar histories grappling with the complex local, national, regional, hemispheric, translocal, transnational, transpacific, interregional, interimperial and global contours of migrant histories (Candela 2016, Delgado 2016).

Diasporic conceptualizations, such as Paul Gilroy's "Black Atlantic" and Henry Yu's "Cantonese Pacific," offer another useful framework capable of grappling with the multispatial realities of migrant histories, particularly when thinking about the activities of migrants whose lives brought together a complex set of social and cultural worlds (Gilroy 1993; Yu 2011). Diasporic concepts help us foreground these complex, multispatial worlds that migrants inhabited and made, worlds that defy bordered histories and geographies. Building on the emerging scholarship on Asians in the Americas and these diasporic approaches, this exhibit employs the concept of ecumene as a framework for conceptualizing the translocal histories and worlds of Asians migrants in the Americas and beyond.

Ecumene, a term used by geographers to describe "worlds of intense and sustained cultural interaction,” offers a way to conceptualize historical geographies that are all too easily eclipsed, erased and even violently destroyed by processes of nation, region and empire making (Comaroff and Comaroff 2000; Dirlik 2005). Engseng Ho’s conceptualization of a transcultural and transregional Islamic ecumene forged by the expansion of a Muslim trade diaspora into the Indian Ocean and beyond beginning in the 13th century offers a rich conceptualization of a diasporic ecumene (Ho 2006). Epili Hau'ofa's description of the Pacific as "Our Sea of Islands" and contemporary Pacific Islander activists' naming of the Pacific as "Oceania" offer other examples of such ecumene (Hau’ofa 1994; Wilson 2016). These Pacific islander ecumene counter hegemonic conceptualizations like the "Pacific Rim" and the "transpacific" in an effort to reclaim the worlds made by islander peoples that have inhabited and voyaged through the region since long before the arrival of European explorers, the unrelenting development rhythms of global capitalism and the destructive phases of militarization brought by US empire.

The reconceptualization of supranational social and cultural spaces as ecumene facilitates historical analyses that are translocal, enabling us to examine human lives and social and cultural worlds situated in relation to a complex set of interconnected historical places, spaces and processes without defaulting back into containing history within the unit of the nation, or some other hegemonic spatial conceptualization that eclipses more than it reveals. As Arif Dirlik suggests, ecumene may even be a productive analogy for conceptualizing the nation, which is always defined through the complex interaction of supranational and subnational dynamics (Dirlik 2005, 407).

This exhibit offers a reading of the The Chinese Colony in Peru as a snapshot of a Cantonese Peruvian ecumene, a translocal world defined by the lives and activities of Cantonese who migrated to Peru during the late 19th and early 20th centuries and who maintained social, cultural and economic ties to many other places and spaces in the world, but particularly to the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong Province in China and to Cantonese migrant communities across the Pacific. It might be more appropriate to imagine this Cantonese Peruvian ecumene as a subecumene, a particular temporal and geographic inflection of a bigger ecumene such as the Cantonese Pacific or a broader Chinese diasporic ecumene constituted through the expansion and fragmentation of Chinese migrant spaces across the world during different periods of time. The idea of a Cantonese Peruvian ecumene is similar to Madeline Hsu’s notion of a Taishanese “elastic community,” a translocal community that spanned from the Toisan-speaking native places in Xinning County of Guangdong Province to San Francisco, and perhaps many other places in the Americas that Taishanese migrated to beginning in the mid-19th century (Hsu 2000). Only, in this case, it is a snapshot of an ecumene approached from the one side of the Pacific, as presented in the album.

Borderlands approaches emphasizing translocal and transnational histories played a critical role in fomenting the recent expansion of scholarship on Asians in the Americas. Scholars working on Asians in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands have produced a number of recent works that shed light on borderlands as a site of intersection between global and local systems of migration, the role of anti-Asian violence in the consolidation of state sovereignty, the rich interracial histories that defy racialized border making, and the formation of ethnic commercial and human trafficking circuits that subvert exclusion acts by moving through borderlands (Romero 2011; Delgado 2012; Schiavone Camacho 2012; García 2014; Chew 2015; Castillo-Muñoz 2016; Chang 2017; Gonzalez 2017). Transpacific and hemispheric frameworks have also played an important role in shaping the new scholarship on Asians in the Americas. These works have situated the history of Chinese coolies in the Americas in relation to hemispheric and Atlantic world histories of black slavery; examined Chinese exclusion acts, Orientalism and yellow peril as hemispheric processes; explored empire as another spatial formation shaping migrant lives; analyzed patterns of remigration across the Americas; and detailed the importance of transpacific homeland ties in shaping Asian lives and identities in the Americas (Azuma 2005; Jung 2006; Yun 2008; Lopez 2013; Schiavone Camacho 2012; Seijas 2014; Young 2014; Lee 2015). This recent scholarship reveals the emerging field of study on Asians in the Americas to be a field defined by efforts to conceptualize migrant histories as multispatial and multiscalar histories grappling with the complex local, national, regional, hemispheric, translocal, transnational, transpacific, interregional, interimperial and global contours of migrant histories (Candela 2016, Delgado 2016).

Diasporic conceptualizations, such as Paul Gilroy's "Black Atlantic" and Henry Yu's "Cantonese Pacific," offer another useful framework capable of grappling with the multispatial realities of migrant histories, particularly when thinking about the activities of migrants whose lives brought together a complex set of social and cultural worlds (Gilroy 1993; Yu 2011). Diasporic concepts help us foreground these complex, multispatial worlds that migrants inhabited and made, worlds that defy bordered histories and geographies. Building on the emerging scholarship on Asians in the Americas and these diasporic approaches, this exhibit employs the concept of ecumene as a framework for conceptualizing the translocal histories and worlds of Asians migrants in the Americas and beyond.

Ecumene, a term used by geographers to describe "worlds of intense and sustained cultural interaction,” offers a way to conceptualize historical geographies that are all too easily eclipsed, erased and even violently destroyed by processes of nation, region and empire making (Comaroff and Comaroff 2000; Dirlik 2005). Engseng Ho’s conceptualization of a transcultural and transregional Islamic ecumene forged by the expansion of a Muslim trade diaspora into the Indian Ocean and beyond beginning in the 13th century offers a rich conceptualization of a diasporic ecumene (Ho 2006). Epili Hau'ofa's description of the Pacific as "Our Sea of Islands" and contemporary Pacific Islander activists' naming of the Pacific as "Oceania" offer other examples of such ecumene (Hau’ofa 1994; Wilson 2016). These Pacific islander ecumene counter hegemonic conceptualizations like the "Pacific Rim" and the "transpacific" in an effort to reclaim the worlds made by islander peoples that have inhabited and voyaged through the region since long before the arrival of European explorers, the unrelenting development rhythms of global capitalism and the destructive phases of militarization brought by US empire.

The reconceptualization of supranational social and cultural spaces as ecumene facilitates historical analyses that are translocal, enabling us to examine human lives and social and cultural worlds situated in relation to a complex set of interconnected historical places, spaces and processes without defaulting back into containing history within the unit of the nation, or some other hegemonic spatial conceptualization that eclipses more than it reveals. As Arif Dirlik suggests, ecumene may even be a productive analogy for conceptualizing the nation, which is always defined through the complex interaction of supranational and subnational dynamics (Dirlik 2005, 407).

This exhibit offers a reading of the The Chinese Colony in Peru as a snapshot of a Cantonese Peruvian ecumene, a translocal world defined by the lives and activities of Cantonese who migrated to Peru during the late 19th and early 20th centuries and who maintained social, cultural and economic ties to many other places and spaces in the world, but particularly to the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong Province in China and to Cantonese migrant communities across the Pacific. It might be more appropriate to imagine this Cantonese Peruvian ecumene as a subecumene, a particular temporal and geographic inflection of a bigger ecumene such as the Cantonese Pacific or a broader Chinese diasporic ecumene constituted through the expansion and fragmentation of Chinese migrant spaces across the world during different periods of time. The idea of a Cantonese Peruvian ecumene is similar to Madeline Hsu’s notion of a Taishanese “elastic community,” a translocal community that spanned from the Toisan-speaking native places in Xinning County of Guangdong Province to San Francisco, and perhaps many other places in the Americas that Taishanese migrated to beginning in the mid-19th century (Hsu 2000). Only, in this case, it is a snapshot of an ecumene approached from the one side of the Pacific, as presented in the album.

The Spaces

The exhibit deconstructs The Chinese Colony in Peru by highlighting a series of spaces that appear in its pages, which together constitute some of the central social, physical and imagined geographic contours of a translocal Cantonese Peruvian ecumene. As revealed by the album, this ecumene was global in scope, in the sense that Cantonese in Peru maintained ties to places across the world, but also in the sense that they lived lives that shaped and were shaped by world-making historical processes. The album does not provide an all-encompassing map of this Cantonese Peruvian ecumene nor of a broader Chinese disaporic world during the early 20th century. It is simply a snapshot of that world crafted by a select group of Cantonese political and economic elite men for a Spanish-speaking and Lima-centered Peruvian political elite male readership. Nonetheless, the spaces that appear in the album offer possibilities for thinking further about the translocal histories of Asians in the Americas and questions of traffic, territory and belonging beyond the nation, the transnational and even the transpacific.

State Space

Keenly aware that Peruvian officials had come perilously close to passing a law restricting Chinese migration in 1922, the group of Cantonese merchants and China Legation officials who compiled The Chinese Colony in Peru crafted it as a tool for self-defense. The album addressed Lima’s political elite. In a gesture to secure state protection for the Chinese community, the album began with an intense visual and textual appeal to state authority. Its opening pages paid homage to distinguished Peruvian political figures, including President Augusto B. Leguia and the Minister of Foreign Affairs Alberto Salomon, but also to the diplomatic officials of the China Legation, such as the Chargé d'affaires Yuming C. Suez, the former Chargé d'affaires Tsung Yee Loo and General Consul Juan F. Iglesias Chin. By paying homage to state authorities, the compilers of the album appealed to Peruvian officials to use their power to protect Chinese migrants’ rights as foreigners to run businesses, "under the protection of [Peruvian] laws, which always provide vast guarantees for their peaceful development (Colonia 1924, 13)."

Appearing at a moment when President Leguia pursued a nation-making agenda driven, in part, by the desire to forge a modern cosmopolitan nation closely tied to the global market with a centralized state, the album appealed to state authority by reminding officials of the economic and patriotic contributions Chinese made to the Peruvian nation. The album reminded Peruvian officials of the taxes and customs fees their import-export businesses contributed to the state treasury. It also reminded Peruvian officials of the many public buildings and monuments that Chinese communities across Peru gifted to local communities, including a locale for the Fiscal School in Huacho, a small plaza in Barranco and a public fountain in Miraflores (21-22). The largest contribution, featured prominently in the introductory pages of the album, was the fountain the Chinese community commissioned in 1921 in commemoration of the nation's centenary for Lima’s Park of the Exposition (21a-21d, 23-24). By commissioning public buildings, plazas and monuments at a moment when the Peruvian state promoted the installation of statuary across the city, part of an effort to assert the growing role of the state in the public sphere in conjunction with an urban modernization program, the merchants behind the album affirmed Leguia’s state-making agendas, positioned themselves as contributors to these state-driven projects and appealed to the Peruvian nation as patriotic subjects. Through the album Chinese elites strategically downplayed their Chinese national identities in order to assert their political and economic rights as foreign residents and to position these rights and themselves in relation to the Peruvian state’s nation building agendas (McKeown 2001, 170).

Appearing at a moment when President Leguia pursued a nation-making agenda driven, in part, by the desire to forge a modern cosmopolitan nation closely tied to the global market with a centralized state, the album appealed to state authority by reminding officials of the economic and patriotic contributions Chinese made to the Peruvian nation. The album reminded Peruvian officials of the taxes and customs fees their import-export businesses contributed to the state treasury. It also reminded Peruvian officials of the many public buildings and monuments that Chinese communities across Peru gifted to local communities, including a locale for the Fiscal School in Huacho, a small plaza in Barranco and a public fountain in Miraflores (21-22). The largest contribution, featured prominently in the introductory pages of the album, was the fountain the Chinese community commissioned in 1921 in commemoration of the nation's centenary for Lima’s Park of the Exposition (21a-21d, 23-24). By commissioning public buildings, plazas and monuments at a moment when the Peruvian state promoted the installation of statuary across the city, part of an effort to assert the growing role of the state in the public sphere in conjunction with an urban modernization program, the merchants behind the album affirmed Leguia’s state-making agendas, positioned themselves as contributors to these state-driven projects and appealed to the Peruvian nation as patriotic subjects. Through the album Chinese elites strategically downplayed their Chinese national identities in order to assert their political and economic rights as foreign residents and to position these rights and themselves in relation to the Peruvian state’s nation building agendas (McKeown 2001, 170).

Cosmopolitan Imaginaries

The fountain donated by the Chinese community to the Park of the Exposition in Lima, which appeared in the album, depicted “nature lavishing her protection upon the races (21a).” Nature, embodied in the figure of a seated woman holding a torch in one hand and a book on her lap with the other, both symbols of knowledge and enlightenment, confidently sat atop the fountain. Several other figures depicting the races of the earth surrounded her, creating a scene of racial hierarchy and uplift that invoked the production of nature, through the practice of agriculture, as a civilizing process. The fountain presented a vision of civilizational uplift and racial progress embraced by President Leguia during the Oncenio (1919-1930). This vision associated Peruvian national and racial progress with the harnessing and distribution of nature’s bounty, which Leguia hoped to fulfill by promoting the development of export-oriented agriculture and natural resource extraction. But the fountain also conveyed messages about the structures of power that underpinned this civilizing vision, communicating messages of racial, spatial and class hierarchies, namely of the domination of the educated, civilized, urban and creole elites over the backwards, rural and laboring peasant mestizos, indios colonos and perhaps even the former black slaves and Chinese coolies who had once labored on Peruvian plantations. Through the act of commissioning and inaugurating the fountain, in response to the Peruvian government’s appeal that foreign communities donate statuary to the new park, Chinese merchant elites situated themselves towards the top of these racial and civilizational hierarchies, positioning themselves as beneficiaries and intermediaries of this civilizing process, particularly in their roles as agriculturalists and merchants who helped produce and distribute Peru’s natural commodities.

The Chinese community also made their own contributions to the fountain’s imaginaries, which they communicated through another set of statues near its base. As they described in the album, "At the bottom there are two figures, one on each side, one representing the rivers of Peru and the other those of China.... blending there to form a single stream. This allegorical symbol, which reveals the fraternity of two peoples, also signals that the rice and silk of the Yangzi Valley have arrived at the banks of the Amazon River, and the coffee and sugar of Chanchamayo Valley have arrived at the ports of the Huanghe River (21a).” The fountain's cosmopolitan message conveyed a sense of civilizational and racial uplift through the commercial interaction of the races of the world via the global circulation of commodities. The fountain suggested that as agents of trade and commerce, Chinese merchants brought China and Peru into contact with one another, advancing the progress of both nations and races. Although partially functioning as an extension of Leguia’s cosmopolitan state-making ideals, the fountain also suggested a Chinese migrant imaginary that had corollaries on the other side of the Pacific, where “Gold Mountain dreams” inspired people to head for the Americas (Hsu 2000). The fountain indicated that Chinese merchants belonged to other worlds, particularly the world of commerce where Chinese trade networks converged with the world of capitalist mass commodity circulations.

The Chinese community also made their own contributions to the fountain’s imaginaries, which they communicated through another set of statues near its base. As they described in the album, "At the bottom there are two figures, one on each side, one representing the rivers of Peru and the other those of China.... blending there to form a single stream. This allegorical symbol, which reveals the fraternity of two peoples, also signals that the rice and silk of the Yangzi Valley have arrived at the banks of the Amazon River, and the coffee and sugar of Chanchamayo Valley have arrived at the ports of the Huanghe River (21a).” The fountain's cosmopolitan message conveyed a sense of civilizational and racial uplift through the commercial interaction of the races of the world via the global circulation of commodities. The fountain suggested that as agents of trade and commerce, Chinese merchants brought China and Peru into contact with one another, advancing the progress of both nations and races. Although partially functioning as an extension of Leguia’s cosmopolitan state-making ideals, the fountain also suggested a Chinese migrant imaginary that had corollaries on the other side of the Pacific, where “Gold Mountain dreams” inspired people to head for the Americas (Hsu 2000). The fountain indicated that Chinese merchants belonged to other worlds, particularly the world of commerce where Chinese trade networks converged with the world of capitalist mass commodity circulations.

Global Capitalist Circuits

Interspersed among the pages featuring predominantly Cantonese merchants, advertisements filled the other pages of The Chinese Colony in Peru, rendering visible the structures that facilitated the flows of industrial capitalism: the banks and finance institutions, the transportation infrastructures and the commercial firms circulating a proliferation of commodities and much needed raw materials throughout the Americas and across the Pacific and Atlantic worlds. The advertisements of transportation firms, like the National Central Railroad of Peru, and of countless import-export firms suggested that Cantonese merchant success and Peruvian national development depended upon the expansion of these flows across vast spaces of the globe, including the Peruvian interior. Praeli Brothers & Co., an import-export firm offering banking services for the major banks of Lima throughout the Peruvian interior, advertised its specialization in the distribution of coffee from Chanchamayo and other Amazonian and Andean commodities. By expanding commodity and capital flows to the internal frontier spaces of national development, firms like Praeli Brothers and Co. helped integrate those spaces into national and global markets, indicating the simultaneous advance of foreign capital and nation making in Peru. Chinese commercial ventures in Peru depended upon but also participated in the expansion of these flows and the integration of these spaces.

The Transatlantic German Bank, which offered wire and money transfer services to places throughout the Spanish-speaking world, informed a Chinese readership in the Chinese language portion of its advertisement that it also offered remittance services to Hong Kong and all of the major coastal ports of China. The Bank of London and Peru appealed to Chinese businessmen by highlighting that a Chinese national employed by the bank would attend to their special needs. Such banks linked Chinese businessmen and capital flows to the hubs of global finance, particularly London and New York, which played prominent roles not only in the global circulation of capital, but also in the incorporation of Peru into the global economy, as it was Britain beginning in the late 19th century and the U.S. after World War I that provided the Peruvian state with the loans needed to stabilize the economy and pursue its nation making agendas. The banks also linked Chinese merchants and Peru to Hong Kong, the British Empire’s eastern Asian colonial entrepôt and the central hub for the flow of Cantonese people, commodities and remittances between China and the Americas (Sinn 2013).

Cantonese merchants in Peru, while partially dependent on Peruvian and foreign-owned commercial, financial and transportation institutions, also established their own infrastructures. An advertisement for the Chungwha Navigation Co., the sole Chinese shipping line formed by a group of prominent Cantonese merchants in Peru, several of whom helped arrange the publication of the album, reveals how these merchants worked to expand capitalist flows to the Southern Pacific and Southeastern Asia. This shipping line linked Peru to Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia and Hong Kong, places where Cantonese commercial networks had flourished since the mid-19th century and where other Chinese commercial networks had thrived since the 16th century. Through the Chungwha venture prominent Cantonese merchants in Lima attempted to forge a southern Pacific commercial circuit that linked South America directly to Asia within a Pacific commercial world dominated by Euro-American and Japanese shipping. This short-lived venture, which collapsed after the implementation of another temporary ban on Chinese migration in 1925, was part of the broader expansion of Chinese commercial circuits into South America and the Caribbean propelled, in part, by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act in the U.S. (Romero 2010).

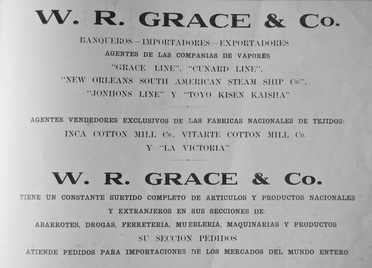

A closer look at the histories of these firms reveals that some had long-standing ties to the Chinese community. W. R. Grace & Co., which advertised it shipping, import-export, commercial and banking services in the album, was the most prominent U.S.-based shipping firm operating in Peru. The firm got its start by shipping Peruvian guano and sugar to the U.S. and Europe, but also by trafficking in Chinese coolies for the American railroad mogul Henry R. Meiggs, who relied on Chinese labor to build his railroads across Peru (Melillo 2015, 130). The darker side of these commercial histories demonstrate how the expansion of global capitalist circuits in Peru, which helped Cantonese commercial networks expand, were themselves built on the backs of the Chinese coolie laborers who mined the guano; grew, harvested, and processed the sugar cane; and built the railroads that made this commercial expansion possible.

The Transatlantic German Bank, which offered wire and money transfer services to places throughout the Spanish-speaking world, informed a Chinese readership in the Chinese language portion of its advertisement that it also offered remittance services to Hong Kong and all of the major coastal ports of China. The Bank of London and Peru appealed to Chinese businessmen by highlighting that a Chinese national employed by the bank would attend to their special needs. Such banks linked Chinese businessmen and capital flows to the hubs of global finance, particularly London and New York, which played prominent roles not only in the global circulation of capital, but also in the incorporation of Peru into the global economy, as it was Britain beginning in the late 19th century and the U.S. after World War I that provided the Peruvian state with the loans needed to stabilize the economy and pursue its nation making agendas. The banks also linked Chinese merchants and Peru to Hong Kong, the British Empire’s eastern Asian colonial entrepôt and the central hub for the flow of Cantonese people, commodities and remittances between China and the Americas (Sinn 2013).

Cantonese merchants in Peru, while partially dependent on Peruvian and foreign-owned commercial, financial and transportation institutions, also established their own infrastructures. An advertisement for the Chungwha Navigation Co., the sole Chinese shipping line formed by a group of prominent Cantonese merchants in Peru, several of whom helped arrange the publication of the album, reveals how these merchants worked to expand capitalist flows to the Southern Pacific and Southeastern Asia. This shipping line linked Peru to Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia and Hong Kong, places where Cantonese commercial networks had flourished since the mid-19th century and where other Chinese commercial networks had thrived since the 16th century. Through the Chungwha venture prominent Cantonese merchants in Lima attempted to forge a southern Pacific commercial circuit that linked South America directly to Asia within a Pacific commercial world dominated by Euro-American and Japanese shipping. This short-lived venture, which collapsed after the implementation of another temporary ban on Chinese migration in 1925, was part of the broader expansion of Chinese commercial circuits into South America and the Caribbean propelled, in part, by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act in the U.S. (Romero 2010).

A closer look at the histories of these firms reveals that some had long-standing ties to the Chinese community. W. R. Grace & Co., which advertised it shipping, import-export, commercial and banking services in the album, was the most prominent U.S.-based shipping firm operating in Peru. The firm got its start by shipping Peruvian guano and sugar to the U.S. and Europe, but also by trafficking in Chinese coolies for the American railroad mogul Henry R. Meiggs, who relied on Chinese labor to build his railroads across Peru (Melillo 2015, 130). The darker side of these commercial histories demonstrate how the expansion of global capitalist circuits in Peru, which helped Cantonese commercial networks expand, were themselves built on the backs of the Chinese coolie laborers who mined the guano; grew, harvested, and processed the sugar cane; and built the railroads that made this commercial expansion possible.

Cantonese Merchant Networks

Cantonese commercial networks grew alongside the expansion of global capitalist circuits in Peru. The establishment of the short-lived Chungwha Navigation Co. revealed that Cantonese commercial networks had grown to the point that a group of Cantonese merchant elites commanded sufficient capital and connections to undertake such a large joint venture. It signals the crystallization of a Cantonese commercial bourgeoisie within the Peruvian Chinese community. The album, the bulk of which presents a series of brief exposés on the individual commercial firms and merchants grouped together by location, offers insights into the formation of this Cantonese Peruvian elite merchant class and the expansion of their commercial networks. The exposés feature photographs and brief biographies of the firm owners and senior personnel, pictures of their commercial houses, plantations and factories, and details about the firms’ origins. Reading across the album for connections between the firms and merchants provides insights into their rhizomatic mode of expansion (Cohen 1997), a preliminary mapping of the territorial extension of Cantonese Peruvian commercial networks and insights regarding their connections to other places of the world.

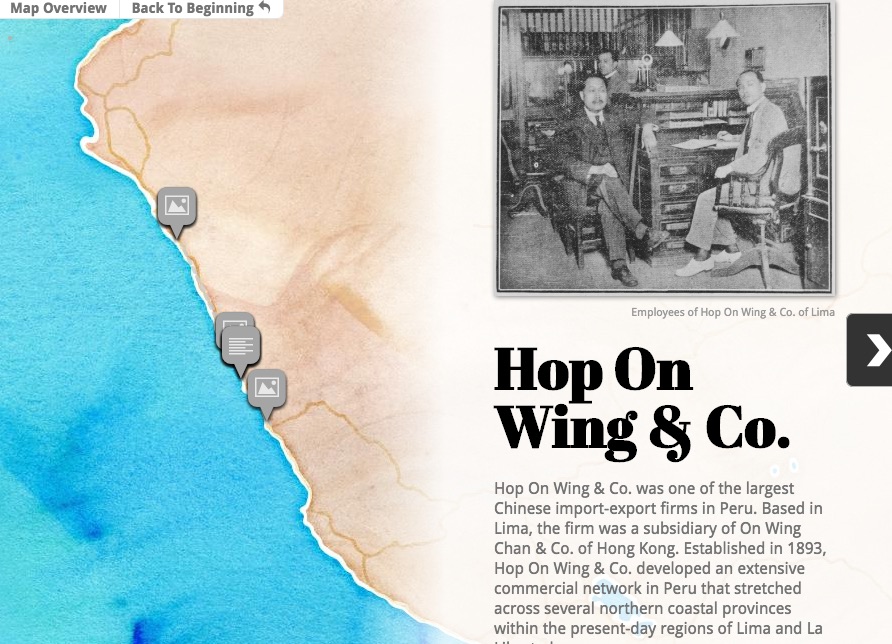

The most prominent of these merchants, including Aurelio Pow San Chia of Pow Lung & Co., Fon Shan King and Cesareo Chin Fuksan of Wing On Chong & Co., Santiago Escudero Whu of Pow On & Co., Pablo Chan Po Lim of Hop On Wing & Co., Tomas Yui Swayne of Wing Yui Chong & Co. and Wing Hing & Co., Jo San Jon of Cheng Hop & Co. and Javier Koo of Kong Fook & Co., all of whom operated the largest Chinese commercial firms in Peru, figured prominently in the “Lima” section of the album. These Lima-based firms had branches, subsidiary firms and personal commercial connections that extended throughout the northern coastal agricultural regions of Lima, Piura, Lambayeque and La Libertad, but also to the southern coastal region of Ica and to Junin. An interior borderland region straddling the Andean highlands and Amazonian rainforest, Junín became closely connected with Lima after Henry Meiggs completed construction of a railroad line to the mining town of La Oroya, facilitating the expansion of commerce, including Cantonese commercial firms, to this highland region. Most of the large Cantonese commercial firms in Peru also maintained strong commercial ties to Hong Kong. Some, like Hop On Wing & Co. (Colonia 1924, 47-50), were subsidiaries of Hong Kong firms, originally established when the Hong Kong parent firm dispatched a trusted employee to undertake a new commercial venture in Lima. These Lima-based firms, which continued to recruit personnel from Hong Kong, would in turn dispatched their own trusted employees to establish branch firms in other Peruvian towns.

The branch firms typically set up shop in towns where a large Chinese population already existed, the remnants of an earlier wave of coolie labor migrations (1849-1874), which brought nearly 100,000 indentured Chinese to labor on Peru’s northern coastal sugar and cotton plantations and to mine guano on the Chincha Islands off the Peruvian coast (Stewart 1951, Rodríguez Pastor 1989, Narvaez 2010). These firms nested into existing Chinese communities and the local commercial networks they had carved out, becoming the chief suppliers of imported Chinese and Japanese commodities, but also offering other foreign commodities (Lausent-Herrera 1983). Cantonese commercial firms in the provinces, like the parent firms in Lima, also took up the trade in general merchandise and groceries, incorporating the sale of Peruvian grains, cattle, pigs and vegetables distributed locally, to Lima and other urban centers. In this way, Cantonese firms became part of an expanding national market for the circulation of everyday commodities (Hu-DeHart 1989). Eventually, senior employees from these branch firms might break away, after having accumulated sufficient experience, reputation, capital and connections to establish their own commercial firms. Maintaining strong commercial relations with the large firms that had once employed them, these newly independent merchants frequently became extensions of the larger firms’ commercial networks.

The largest of these firms and merchants also expanded into plantation agriculture, producing sugar and cotton for export at a time when these mass commodities were in high demand in the industrial centers of Europe and the United States, but also in places like Shanghai with its growing textile industry. This expansion into export oriented agricultural production was a pivotal factor fueling the growth of Cantonese commercial networks throughout Peru and the consolidation of a Cantonese elite merchant class. With the rapid extension of Cantonese commercial networks across the northern coastal agricultural regions of Peru, an expansion that began at the end of the 19th century and intensified during the inter-war period, Cantonese merchant elites turned their attention to strengthening their commercial networks with other Chinese communities across the Pacific, and to building their own shipping infrastructure, as evidenced by the establishment of the short-lived Chungwha Navigation Co. Their commercial trajectories had come full circle.

The most prominent of these merchants, including Aurelio Pow San Chia of Pow Lung & Co., Fon Shan King and Cesareo Chin Fuksan of Wing On Chong & Co., Santiago Escudero Whu of Pow On & Co., Pablo Chan Po Lim of Hop On Wing & Co., Tomas Yui Swayne of Wing Yui Chong & Co. and Wing Hing & Co., Jo San Jon of Cheng Hop & Co. and Javier Koo of Kong Fook & Co., all of whom operated the largest Chinese commercial firms in Peru, figured prominently in the “Lima” section of the album. These Lima-based firms had branches, subsidiary firms and personal commercial connections that extended throughout the northern coastal agricultural regions of Lima, Piura, Lambayeque and La Libertad, but also to the southern coastal region of Ica and to Junin. An interior borderland region straddling the Andean highlands and Amazonian rainforest, Junín became closely connected with Lima after Henry Meiggs completed construction of a railroad line to the mining town of La Oroya, facilitating the expansion of commerce, including Cantonese commercial firms, to this highland region. Most of the large Cantonese commercial firms in Peru also maintained strong commercial ties to Hong Kong. Some, like Hop On Wing & Co. (Colonia 1924, 47-50), were subsidiaries of Hong Kong firms, originally established when the Hong Kong parent firm dispatched a trusted employee to undertake a new commercial venture in Lima. These Lima-based firms, which continued to recruit personnel from Hong Kong, would in turn dispatched their own trusted employees to establish branch firms in other Peruvian towns.

The branch firms typically set up shop in towns where a large Chinese population already existed, the remnants of an earlier wave of coolie labor migrations (1849-1874), which brought nearly 100,000 indentured Chinese to labor on Peru’s northern coastal sugar and cotton plantations and to mine guano on the Chincha Islands off the Peruvian coast (Stewart 1951, Rodríguez Pastor 1989, Narvaez 2010). These firms nested into existing Chinese communities and the local commercial networks they had carved out, becoming the chief suppliers of imported Chinese and Japanese commodities, but also offering other foreign commodities (Lausent-Herrera 1983). Cantonese commercial firms in the provinces, like the parent firms in Lima, also took up the trade in general merchandise and groceries, incorporating the sale of Peruvian grains, cattle, pigs and vegetables distributed locally, to Lima and other urban centers. In this way, Cantonese firms became part of an expanding national market for the circulation of everyday commodities (Hu-DeHart 1989). Eventually, senior employees from these branch firms might break away, after having accumulated sufficient experience, reputation, capital and connections to establish their own commercial firms. Maintaining strong commercial relations with the large firms that had once employed them, these newly independent merchants frequently became extensions of the larger firms’ commercial networks.

The largest of these firms and merchants also expanded into plantation agriculture, producing sugar and cotton for export at a time when these mass commodities were in high demand in the industrial centers of Europe and the United States, but also in places like Shanghai with its growing textile industry. This expansion into export oriented agricultural production was a pivotal factor fueling the growth of Cantonese commercial networks throughout Peru and the consolidation of a Cantonese elite merchant class. With the rapid extension of Cantonese commercial networks across the northern coastal agricultural regions of Peru, an expansion that began at the end of the 19th century and intensified during the inter-war period, Cantonese merchant elites turned their attention to strengthening their commercial networks with other Chinese communities across the Pacific, and to building their own shipping infrastructure, as evidenced by the establishment of the short-lived Chungwha Navigation Co. Their commercial trajectories had come full circle.

By mapping the merchants, agriculturalists, commercial firms and associations featured in The Chinese Colony in Peru, we can better visualize the extensive commercial networks Cantonese merchants formed across the northern coastal agricultural regions of Peru, their expansion from commerce to agriculture, their strategic movement into the borderland regions of the country, their role in the expansion of a national market integrated with the global economy and the rhizomatic and translocal dimensions of their commercial networks.

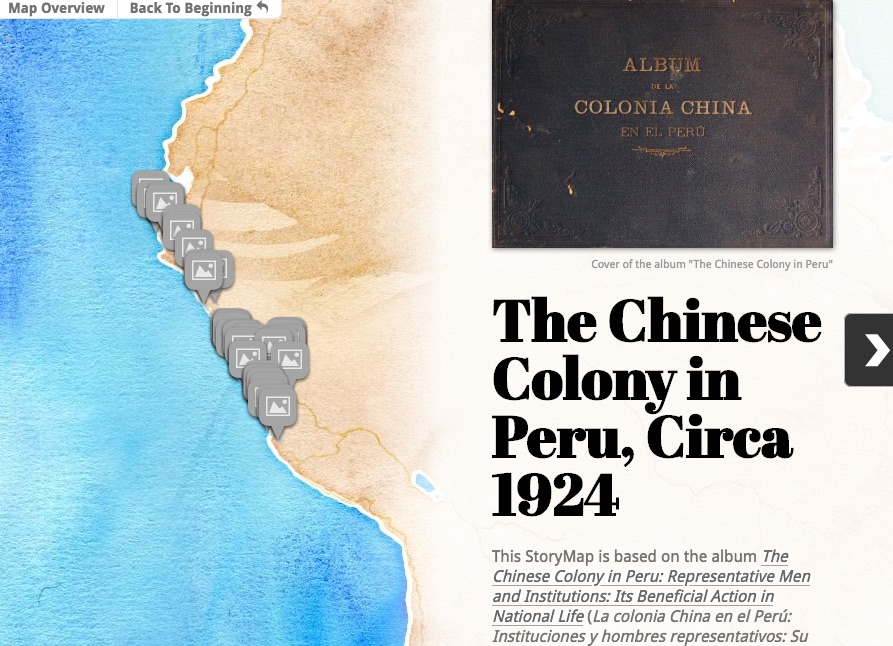

StoryMap 1 offers a comprehensive mapping of the different merchant communities located predominantly along Peru's northern coastal regions, roughly following the spatial organization provided in The Chinese Colony in Peru. Readers can move through the map as a way to explore the individual firms and merchants featured in the album. Links throughout the map connect readers to the album’s Spanish-language exposés of Cantonese merchants and their firms.

StoryMap 2 offers a mapping of the commercial network established by the Lima-based firm Hop On Wing & Co., one of the largest Cantonese commercial firms in Peru and a subsidiary of the Hong Kong-based On Wing Chan & Co. It demonstrates how in reading the exposés in The Chinese Colony in Peru for connections between the firms and merchants, readers can reconstruct the formation of particular Cantonese commercial networks as they took form through the movements of firm owners, employees and associates. Such mappings reveal how Cantonese commercial networks functioned simultaneously as structures of mobility and settlement, playing an important role in the formation of a translocal Cantonese Peruvian ecumene.

StoryMap 1 offers a comprehensive mapping of the different merchant communities located predominantly along Peru's northern coastal regions, roughly following the spatial organization provided in The Chinese Colony in Peru. Readers can move through the map as a way to explore the individual firms and merchants featured in the album. Links throughout the map connect readers to the album’s Spanish-language exposés of Cantonese merchants and their firms.

StoryMap 2 offers a mapping of the commercial network established by the Lima-based firm Hop On Wing & Co., one of the largest Cantonese commercial firms in Peru and a subsidiary of the Hong Kong-based On Wing Chan & Co. It demonstrates how in reading the exposés in The Chinese Colony in Peru for connections between the firms and merchants, readers can reconstruct the formation of particular Cantonese commercial networks as they took form through the movements of firm owners, employees and associates. Such mappings reveal how Cantonese commercial networks functioned simultaneously as structures of mobility and settlement, playing an important role in the formation of a translocal Cantonese Peruvian ecumene.

The Rural-Urban Divide

As Cantonese merchants expanded into sugar and cotton production, they became part of a growing rural-urban divide reshaping Peru’s northern coastal agricultural valleys. The construction of this rural-urban divide resulted from several conjoined processes: the expansion of towns across Peru into regional commercial hubs, the industrialization of rural production and the romanticization of rural imaginaries. These processes were part of a broader restructuring of rural social relations brought about as the logics of industrial capitalism continued to penetrate the countryside, which included the transformation of the campesino (peasant) into a proletarianized wage laborer, the introduction of machinery to accelerate agricultural production and the employment of engineers to rationalize and maximize production. Photographs and descriptions of Cantonese owned or operated plantations portrayed them as modern enterprises of rational and engineered oversight that maximized the production of agricultural commodities for export, contributed to national economic development and improved the conditions of workers.

The album also presented readers with romantic images of the plantations, depicting them as spaces where cattle and dogs roamed and Cantonese hacendados (plantation owners) and their families enjoyed gardens, strolling, hunting and horseback riding. When contrasted with the numerous photographs of urban commercial firms and Cantonese businessmen in suits, these images depict plantations as idyllic spaces of unspoiled natural landscapes and leisure. The pastoral scenes naturalize the social transformations taking place in the countryside, masking the darker side of those changes, including labor unrest and land enclosures. The photographs also communicated another important message: Cantonese merchants had become settlers. Following the trajectories of an earlier wave of European migrants, Cantonese arrived as merchants and became plantation owners and settled immigrants with families. The pictures suggested a trajectory of localization, of Chinese immigrants becoming Peruvian.

The album also presented readers with romantic images of the plantations, depicting them as spaces where cattle and dogs roamed and Cantonese hacendados (plantation owners) and their families enjoyed gardens, strolling, hunting and horseback riding. When contrasted with the numerous photographs of urban commercial firms and Cantonese businessmen in suits, these images depict plantations as idyllic spaces of unspoiled natural landscapes and leisure. The pastoral scenes naturalize the social transformations taking place in the countryside, masking the darker side of those changes, including labor unrest and land enclosures. The photographs also communicated another important message: Cantonese merchants had become settlers. Following the trajectories of an earlier wave of European migrants, Cantonese arrived as merchants and became plantation owners and settled immigrants with families. The pictures suggested a trajectory of localization, of Chinese immigrants becoming Peruvian.

Intimate Spaces

Although most merchants contributed photographs of themselves, their employees and their commercial firms for publication in the album, a few contributed family photographs. Aurelio Pow San Chia, who is regarded as one of the founding figures of the Chinese community in Peru, set the example by prominently featuring his family and the interior spaces of his home in the introductory section of the album (Colonia 1924, 31-33). Through such pictures, Cantonese merchant elites depicted themselves as settlers, emphasizing they had established families and roots in Peru. The photographs also helped merchants lay claim to elite status, demonstrating they observed the same bourgeois lifestyles and standards of taste as Lima's upper classes. By rendering visible the domestic sphere, which was conventionally the less visible, interior and gendered sphere of women, the photographs presented Cantonese merchants’ domestic lives as a site of social, cultural and racial mestizaje and also revealed how kinship served as a mechanism of localization (Lausent-Herrera 1983; Derpich 1999; Delgado 2012). Aurelio Pow San Chia, for example, published a picture of his mixed-race family, including his Peruvian wife and their two adopted Peruvian children, who were originally his wife's niece and nephew. His adopted daughter is also pictured with her husband Aurelio Chin Fuksan, a trusted employee of Aurelio Pow San Chia’s firm, and their mixed-race daughter, who heralded the arrival of a new generation of mixed-race Cantonese Peruvian offspring.

By contrast, Ali Luzula, the only merchant to present a picture of his children in Hong Kong, offered the album’s readership an orientalized snapshot of respectable family life on the other side of the Pacific. The picture of Luzula's children offers us a glimpse into an otherwise eclipsed transpacific dimension of Cantonese merchants’ family life, as it was quite common for successful men to journey back to their native places to secure brides and to produce offspring. It was also common for these men to send their Peruvian-born offspring to be raised and educated in their native places, to ensure a Cantonese social and cultural upbringing. With the exception of Luzula’s family photograph, the lack of representation of this important dimension of Cantonese Peruvian life in the album reemphasized a message of settlement. It revealed that The Chinese Colony in Peru was an exercise in self-fashioning in alignment with the settler imaginaries that drove Peruvian nation making, in which the bourgeois nuclear family figured as the ideal social unit. These family pictures eclipsed but did not alter the reality that many Cantonese merchants belonged to disaporic families. In practice, Cantonese businesses, personal success and notions of respectability depended upon the maintenance of transpacific family and business networks with complex gendered, generational and translocal divisions of labor (Mazumdar 2003). This is one of many other dimensions of a broader Cantonese Peruvian ecumene missing from the album.

By contrast, Ali Luzula, the only merchant to present a picture of his children in Hong Kong, offered the album’s readership an orientalized snapshot of respectable family life on the other side of the Pacific. The picture of Luzula's children offers us a glimpse into an otherwise eclipsed transpacific dimension of Cantonese merchants’ family life, as it was quite common for successful men to journey back to their native places to secure brides and to produce offspring. It was also common for these men to send their Peruvian-born offspring to be raised and educated in their native places, to ensure a Cantonese social and cultural upbringing. With the exception of Luzula’s family photograph, the lack of representation of this important dimension of Cantonese Peruvian life in the album reemphasized a message of settlement. It revealed that The Chinese Colony in Peru was an exercise in self-fashioning in alignment with the settler imaginaries that drove Peruvian nation making, in which the bourgeois nuclear family figured as the ideal social unit. These family pictures eclipsed but did not alter the reality that many Cantonese merchants belonged to disaporic families. In practice, Cantonese businesses, personal success and notions of respectability depended upon the maintenance of transpacific family and business networks with complex gendered, generational and translocal divisions of labor (Mazumdar 2003). This is one of many other dimensions of a broader Cantonese Peruvian ecumene missing from the album.

Conclusion

The album offers a snapshot, a temporally and spatially limited glimpse, of a Cantonese Peruvian ecumene strategically crafted to claim social and economic inclusion in Peru without claiming political citizenship. Published at a moment when the threat of Chinese exclusion promised to disrupt that ecumene, the album's narrative hid as much as it revealed, obscuring traces of Cantonese migrant social and cultural practices and downplaying Chinese national belonging in an effort to emphasize localization. The consolidation of settler nation states forged, in part, through Asian exclusion acts across the Americas and the Pacific had supranational implications, affecting things like the expansion of Chinese commercial circuits into South America and the Caribbean during the era of the Chinese Exclusion Act in the U.S., or the severing of the short-lived Southern Pacific Chinese commercial circuit that linked Latin America and Asia via the Chungwha Navigation Co. after Peru temporarily restricted Chinese migration in 1925, or even the reorientation of Cantonese native place networks and notions of national belonging towards Taiwan after the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949 and throughout the Cold War era (González, 2017). Thinking about traffics, territories and belonging from a world-historical approach to the study of Asians in the Americas compels us to not lose sight of diasporic geographies that persist, although in constantly shifting dimensions, despite the intensification of nation making. A world-historical approach challenges us to examine the shifting translocal rhythms, routes and spaces of the diasporic ecumene that Chinese migrants made. It also challenges us to explore the global dimensions of these Chinese migrant worlds by examining the ways in which they constitute and are constituted by world-historical processes.

Works Cited

Azuma, Eiichiro. Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Candela, Ana Maria. “The Politics of Imagining Asia from the Periphery: Orientalism, Yellow Peril, and Hegemony in the Peruvian Aristocratic Republic, 1895-1930,” working paper. “Anti-Asian Publics and Latin American Transformations: The Political Power of Yellow Peril in the Darker Nations” panel at the 2016 Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association annual meeting, Waikoloa, Hawaii, August 5, 2016.

Castillo-Muñoz, Veronica. The Other California: Land Identity and Politics on the Mexican Borderlands. University of California Press, forthcoming 2016.

Chang, Jason Oliver. Chino: Racial Transformation of the Chinese in Mexico, 1880-1940. University of Illinois Press, forthcoming 2017.

Chew, Selfa A. Uprooting Community: Japanese Mexicans, World War II, and the US-Mexico Borderlands. University of Arizona Press, 2015.

Colonia China en el Perú. La Colonia China en el Perú: Instituciones y Hombres Representativos: Su Actuación Benéfica en la Vida Nacional. Lima: Sociedad Editorial Panamericana, 1924.

Cohen, Robin. “Diasporas, the Nation-State and Globalisation.” In Global History and Migrations, edited by Wang Gungwu, 117-143. Westview Press, 1997.

Comaroff, Jean and John L. Comaroff. "Millennial Capitalism: First Thoughts On a Second Coming." Public Culture 12, no. 2 (2000): 291-343.

Delgado, Grace Peña. “Globalizing Asias: A Multiscalar Approach to Immigration and Inter-Ethnic History,” a working paper. “Anti-Asian Publics and Latin American Transformations: The Political Power of Yellow Peril in the Darker Nations” panel at the 2016 Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association annual meeting, Waikoloa, Hawaii, August 5, 2016.

_____. Making the Chinese Mexican: Global Migration, Localism and Exclusion in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands. Stanford University Press, 2012.

Derpich, Wilma E. “El Otro Lado Azul”: Empresarios Chinos en el Perú. Lima: Congreso del Perú. 1999.

Dirlik, Arif. "Performing the World: Reality and Representation in the Making of World Histor(ies)." Journal of World History 16, no. 4 (2005): 391-410.

García, Jerry. Looking Like the Enemy: Japanese Mexicans, the Mexican State, and US Hegemony, 1897-1945. University of Arizona Press, 2014.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Harvard University Press, 1993.

González, Fredy. Paisanos Chinos: Transpacific Politics Among Chinese Immigrants in Mexico. University of California Press, forthcoming 2017.

Hau’ofa, Epili. "Our Sea of Islands." The Contemporary Pacific (1994): 148-161.

Ho, Engseng. The Graves of Tarim: Genealogy and Mobility Across the Indian Ocean. University of California Press, 2006.

Hoffecker, Carol E. "The Emergence of a Genre: The Urban Pictorial History." The Public Historian 5, no. 4 (1983): 37-48.

Hsu, Madeline Y. Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration Between the United States and South China, 1882-1943. Stanford University Press, 2000.

Hu-DeHart, Evelyn. “Coolies, Shopkeepers and Pioneers: The Chinese of Mexico and Peru (1849-1930).” Amerasia Journal 15, No. 2 (1989): 91-116.

Jung, Moon-Ho. Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Lausent-Herrera, Isabelle. Sociedades y Templos Chinos en el Perú. Lima: Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú, 2000.

_____. Pequeña Propiedad, Poder y Economia de Mercado: Acos, Valle del Chancay. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 1983.

Lee, Erika. The Making of Asian America: A History. Simon and Schuster, 2015.

López, Kathleen. Chinese Cubans: A Transnational History. University of North Carolina Press Books, 2013.

Mazumdar, Sucheta. "What Happened to the Women? Chinese and Indian Male Migration to the United States in Global Perspective." In Asian/Pacific Islander American Women: A Historical Anthology, edited by Shirley Hune and Gail M. Nomura, 58-76. New York University Press, 2003.

McKeown, Adam. Chinese Migrant Networks and Cultural Change: Peru, Chicago, and Hawaii 1900-1936. University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Melillo, Edward Dallam. Strangers on Familiar Soil: Rediscovering the Chile-California Connection. Yale University Press, 2015.

Narvaez, Benjamin Nicolas. "Chinese Coolies in Cuba and Peru: Race, Labor, and Immigration, 1839-1886." Ph.D. diss., The University of Texas at Austin, 2010.

Rodríguez Pastor, Humberto. Hijos del Celeste Imperio en el Perú (1850-1900): Migración, Agricultura, Mentalidad y Explotación. Lima: Instituto de Apoyo Agrario, 1989.

Romero, Robert Chao. The Chinese in Mexico, 1882-1940. University of Arizona Press, 2011.

Schiavone Camacho, Julia María. Chinese Mexicans: Transpacific Migration and the Search For a Homeland, 1910-1960. University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Seijas, Tatiana. Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Sinn, Elizabeth. Pacific Crossing: California Gold, Chinese Migration, and the Making of Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press, 2012.

Stewart, Watt. Chinese Bondage in Peru. Duke University Press, 1951.

Young, Elliott. Alien Nation: Chinese Migration in the Americas from the Coolie Era Through World War II. University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Wilson, Rob. "Towards an Ecopoetics of Oceania: Worlding the Asia-Pacific Region as Space-Time Ecumene." In American Studies as Transnational Practice, edited by Yuan Shu and Donald E. Pease, 213-236. Dartmouth College Press, 2016.

Young, David W. “’You Feel So Out of Place’: Germantown's J. Gordon Baugh and the 1913 Commemoration of the Emancipation Proclamation," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 137, no. 1 (2013): 79-93.

Yu, Henry. "The Intermittent Rhythms of the Cantonese Pacific." In Connecting Seas and Connected Ocean Rims: Indian, Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and China Seas Migrations from 1830s to the 1930s, edited by Donna R. Gabaccia and Dirk Hoerder, 393-414. Brill, 2011.

Yun, Lisa. The Coolie Speaks: Chinese Indentured Laborers and African Slaves in Cuba. Temple University Press, 2008.

Candela, Ana Maria. “The Politics of Imagining Asia from the Periphery: Orientalism, Yellow Peril, and Hegemony in the Peruvian Aristocratic Republic, 1895-1930,” working paper. “Anti-Asian Publics and Latin American Transformations: The Political Power of Yellow Peril in the Darker Nations” panel at the 2016 Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association annual meeting, Waikoloa, Hawaii, August 5, 2016.

Castillo-Muñoz, Veronica. The Other California: Land Identity and Politics on the Mexican Borderlands. University of California Press, forthcoming 2016.

Chang, Jason Oliver. Chino: Racial Transformation of the Chinese in Mexico, 1880-1940. University of Illinois Press, forthcoming 2017.

Chew, Selfa A. Uprooting Community: Japanese Mexicans, World War II, and the US-Mexico Borderlands. University of Arizona Press, 2015.

Colonia China en el Perú. La Colonia China en el Perú: Instituciones y Hombres Representativos: Su Actuación Benéfica en la Vida Nacional. Lima: Sociedad Editorial Panamericana, 1924.

Cohen, Robin. “Diasporas, the Nation-State and Globalisation.” In Global History and Migrations, edited by Wang Gungwu, 117-143. Westview Press, 1997.

Comaroff, Jean and John L. Comaroff. "Millennial Capitalism: First Thoughts On a Second Coming." Public Culture 12, no. 2 (2000): 291-343.

Delgado, Grace Peña. “Globalizing Asias: A Multiscalar Approach to Immigration and Inter-Ethnic History,” a working paper. “Anti-Asian Publics and Latin American Transformations: The Political Power of Yellow Peril in the Darker Nations” panel at the 2016 Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association annual meeting, Waikoloa, Hawaii, August 5, 2016.

_____. Making the Chinese Mexican: Global Migration, Localism and Exclusion in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands. Stanford University Press, 2012.

Derpich, Wilma E. “El Otro Lado Azul”: Empresarios Chinos en el Perú. Lima: Congreso del Perú. 1999.

Dirlik, Arif. "Performing the World: Reality and Representation in the Making of World Histor(ies)." Journal of World History 16, no. 4 (2005): 391-410.

García, Jerry. Looking Like the Enemy: Japanese Mexicans, the Mexican State, and US Hegemony, 1897-1945. University of Arizona Press, 2014.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Harvard University Press, 1993.

González, Fredy. Paisanos Chinos: Transpacific Politics Among Chinese Immigrants in Mexico. University of California Press, forthcoming 2017.

Hau’ofa, Epili. "Our Sea of Islands." The Contemporary Pacific (1994): 148-161.

Ho, Engseng. The Graves of Tarim: Genealogy and Mobility Across the Indian Ocean. University of California Press, 2006.

Hoffecker, Carol E. "The Emergence of a Genre: The Urban Pictorial History." The Public Historian 5, no. 4 (1983): 37-48.

Hsu, Madeline Y. Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration Between the United States and South China, 1882-1943. Stanford University Press, 2000.

Hu-DeHart, Evelyn. “Coolies, Shopkeepers and Pioneers: The Chinese of Mexico and Peru (1849-1930).” Amerasia Journal 15, No. 2 (1989): 91-116.

Jung, Moon-Ho. Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Lausent-Herrera, Isabelle. Sociedades y Templos Chinos en el Perú. Lima: Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú, 2000.

_____. Pequeña Propiedad, Poder y Economia de Mercado: Acos, Valle del Chancay. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 1983.

Lee, Erika. The Making of Asian America: A History. Simon and Schuster, 2015.

López, Kathleen. Chinese Cubans: A Transnational History. University of North Carolina Press Books, 2013.

Mazumdar, Sucheta. "What Happened to the Women? Chinese and Indian Male Migration to the United States in Global Perspective." In Asian/Pacific Islander American Women: A Historical Anthology, edited by Shirley Hune and Gail M. Nomura, 58-76. New York University Press, 2003.

McKeown, Adam. Chinese Migrant Networks and Cultural Change: Peru, Chicago, and Hawaii 1900-1936. University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Melillo, Edward Dallam. Strangers on Familiar Soil: Rediscovering the Chile-California Connection. Yale University Press, 2015.

Narvaez, Benjamin Nicolas. "Chinese Coolies in Cuba and Peru: Race, Labor, and Immigration, 1839-1886." Ph.D. diss., The University of Texas at Austin, 2010.

Rodríguez Pastor, Humberto. Hijos del Celeste Imperio en el Perú (1850-1900): Migración, Agricultura, Mentalidad y Explotación. Lima: Instituto de Apoyo Agrario, 1989.

Romero, Robert Chao. The Chinese in Mexico, 1882-1940. University of Arizona Press, 2011.

Schiavone Camacho, Julia María. Chinese Mexicans: Transpacific Migration and the Search For a Homeland, 1910-1960. University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Seijas, Tatiana. Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Sinn, Elizabeth. Pacific Crossing: California Gold, Chinese Migration, and the Making of Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press, 2012.

Stewart, Watt. Chinese Bondage in Peru. Duke University Press, 1951.

Young, Elliott. Alien Nation: Chinese Migration in the Americas from the Coolie Era Through World War II. University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Wilson, Rob. "Towards an Ecopoetics of Oceania: Worlding the Asia-Pacific Region as Space-Time Ecumene." In American Studies as Transnational Practice, edited by Yuan Shu and Donald E. Pease, 213-236. Dartmouth College Press, 2016.

Young, David W. “’You Feel So Out of Place’: Germantown's J. Gordon Baugh and the 1913 Commemoration of the Emancipation Proclamation," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 137, no. 1 (2013): 79-93.

Yu, Henry. "The Intermittent Rhythms of the Cantonese Pacific." In Connecting Seas and Connected Ocean Rims: Indian, Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and China Seas Migrations from 1830s to the 1930s, edited by Donna R. Gabaccia and Dirk Hoerder, 393-414. Brill, 2011.

Yun, Lisa. The Coolie Speaks: Chinese Indentured Laborers and African Slaves in Cuba. Temple University Press, 2008.

© COPYRIGHT 2023. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.